Sorting Mined Ore Not A Mere Scheme: And Other Lessons In Patentable Subject Matter

10/04/20

Lily Brennan-Xie and Sam Mickan, Davies Collison Cave

The Federal Court of Australia has allowed an appeal in favour of patent applicant and appellant Technological Resources Pty Ltd (a subsidiary of Rio Tinto) by dismissing an opposition decision of a Delegate of the Commissioner of Patents.

This case is of particular interest as it flies in the face of recent cases invalidating patents on the basis that they did not relate to patentable subject matter. Justice Jagot, accepting all of Technological Resources’ submissions on this issue, found that the series of physical steps involved in its invention produced a ‘physical and tangible result’. Therefore, they could not be described as a mere scheme, mere working directions, or a mere collocation of parts with no functional interdependence — none of which are patentable. The claimed invention was, contrary to the finding of the Delegate, a manner of manufacture and therefore a patentable invention under s 18(1)(a) of the Patents Act.

Curiously, the respondent did not initially raise lack of patentable subject matter as a ground of opposition in the proceeding before the Delegate of the Commissioner. Rather, the Delegate exercised his power under s 60(3) of the Patents Act to take into account a ground of opposition not relied on by the opponent.[1]

THE INVENTION

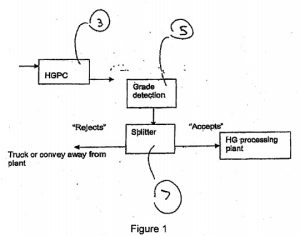

Claim 1 of Technological Resources’ patent application (2011261171) was for a method of mining that included the following steps (with references in brackets to the Figure below):

(a) mining ore;

(b) reducing the size of the mined ore in a crushing step and producing a crushed ore having a primary crushed ore particle size (in high grade primary crusher circuit 3);

(c) assessing the grade of successive segments of the crushed ore by direct assessment of grade as the crushed ore is transported along a pathway (at grade assessment assembly 5);

(d) separating each segment of the crushed ore on the basis of grade of the segment into a category that is at or above a first grade threshold or a category that is below the first grade threshold by dry sorting the segment (at sorter 7 in the form of a splitter system); and

(e) processing separated segments in a downstream processing plant and producing upgraded material.

Other claims related to an apparatus for separating a mined ore that carries out steps similar to (b)-(e).

FEDERAL COURT APPEAL

Tom Cordiner QC and Clare Cunliffe, on behalf of Tettman (who is a registered patent attorney and is presumably acting as a straw man opponent on behalf of an anonymous third party), argued that the claimed invention was not patentable because it fell into at least one of a number of broad categories that do not constitute patentable subject matter. These categories include ‘mere schemes’, ‘mere collocations’ and ‘mere working directions’. With respect to the arguments that the claimed invention was a mere scheme and related to no more than mere working directions, Tettman appears to have made no submissions — instead relying entirely on the reasons of the Delegate.

Jagot J disagreed on all accounts in favour of the submissions made by Christian Dimitriadis SC and Julian Cooke for Technological Resources. Her Honour’s extensive acceptance and use of these submissions in her judgement may confine the applicability of this decision to the claims in question. However, the takeaways are positive for patent applicants — especially those whose inventions involve a combination of physical steps that give rise to a physical and tangible result.

FOCUS ON THE COMBINATION

Jagot J’s consideration of the claimed apparatus and series of steps suggests that for combination patents, where the combination is new, the focus should be shifted away from components or steps in isolation.[2] Technological Resources’ submissions, accepted by Her Honour, outline that whether the interaction between the steps or components (each of which may or may not be new) produces a ‘new and useful result’ is relevant.[3] This is based on the High Court’s watershed decision in NRDC.[4]

Her Honour found that the claims involved a functionally integrated combination of steps that could not be described as a ‘mere collocation’. A ‘mere collocation’ of parts that each serve their own separate function is not patentable subject matter.[5] However, Jagot J agreed with Technological Resources that the claimed invention was not ‘a combination of parts’ at all. Rather, it was a method and apparatus involving sequential and interrelated steps for the processing of ore. The fact that individual steps or components could operate in the absence of the others did not render the invention a mere collocation. It was satisfactory that each subsequent step depended on the creation of a ‘new state of affairs’ by the preceding step.[6] In this context, ‘new’ appears to be unrelated to novelty concepts but rather relates to the output of each step (e.g., ‘ore is mined’).

Additionally, Jagot J disagreed with the Delgate’s finding that the claimed steps were ‘mere working directions’ because they were only generally described and were obvious or routine.[7] Her Honour accepted that the Delegate reached his conclusion by erroneously focusing on each step of this invention in isolation. Again, she emphasised that the focus must be on the combination as claimed. With the correct view of the invention as a combination, both the evidence and the specification demonstrated that the claimed combination was new. Therefore, the principle of ‘mere working directions’ did not apply.

MERE SCHEME?

The Delegate was guided by Research Affiliates[8] and RPL Central[9] in his decision that the invention’s use of ‘generic’ technology and lack of specific ‘technical components’ made it ‘clear’ that the invention was a mere scheme.[10]

Jagot J did not agree. Her Honour did not consider the application of these ‘mere scheme cases’ was appropriate in light of the nature of the invention at hand. Instead, she accepted Technological Resources’ view that where a method is not a computer implementation of an otherwise unpatentable business method or scheme, the mere scheme cases do not apply. In particular, Technical Resources’ invention did not resemble those of the mere scheme cases — it involved ‘physical steps carried out on a physical product using physical apparatus, to produce a physical and tangible result’.[11]

It may be a consequence of such reasoning that where the ‘mere scheme cases’ do not apply, the use of generic technology will not exclude an invention from patentability. In other words, a general description of steps or components could be sufficient. This will especially be the case for inventions rooted in the physical realm, i.e., involving ‘physical steps carried out on a physical product using physical apparatus, to produce a physical and tangible result’.

CURTAILING THE REACH OF THE MANNER OF MANUFACTURE OBJECTION

The Patent Office often purports to rely on RPL Central and Research Affiliates when identifying matters relevant to determining whether a claimed invention relates to patentable subject matter, such as:

- Is the contribution to the claimed invention technical in nature?

- Does the claimed invention solve a “technical” problem within the computer or outside the computer?

- Does the claimed invention result in an improvement in the functioning of the computer, irrespective of the data being processed?

- Does the claimed invention merely require generic computer implementation?

- Is the computer merely the intermediary, configured to carry out the method, but adding nothing to the substance of the idea?

While the ‘mere scheme cases’ have been involved in the downfall of certain software patents in recent times,[12] Technological Resources Pty Ltd v Tettman makes it clear that the principles these cases stand for do not have infinite reach.

When it comes to physical steps, physical apparatus and physical results, the mere ‘generic’ nature of any component of an invention is unlikely to prevent it from being patentable subject matter. Again, the focus of the enquiry must be on each claim as a whole, accounting for the fact that a new combination of known features may be patentable subject matter.

What remains to be clarified is why the courts and the Patent Office seem to be holding computer implemented inventions to a different standard to other inventions. Should principles applied in this case, such as the emphasis that each invention must be considered as a whole, apply to computer-implemented inventions where the components of the computer and/or the steps carried out are known or generic, but the combination is new and produces a useful result? The Full Court may shed some light when it hands down its reserved judgement in Commissioner of Patents v Rokt Pte Ltd later this year.[13]

Solicitor for the appellant: Minter Ellison

Solicitor for the respondent: Herbert Smith Freehills

Authors: Lily Brennan-Xie, Trainee Patent Attorney

and Sam Mickan, Principal

[1] Tettman v Technological Resources Pty Ltd [2018] APO 22 [154].

[2] Technological Resources Pty Ltd v Tettman [2019] FCA 1889 [134]–[136], [157]–[159].

[3] Technological Resources Pty Ltd v Tettman [2019] FCA 1889 [135], [157].

[4] National Research Development Corporation v Commissioner of Patents (1959) 102 CLR 252.

[5] British Celanese Ltd v Courtaulds Ltd (1935) 52 RPC 171 193–194.

[6] Technological Resources Pty Ltd v Tettman [2019] FCA 1889 [140].

[7] Tettman v Technological Resources Pty Ltd [2018] APO 22 [172].

[8] Research Affiliates LLC v Commissioner of Patents [2014] FCAFC 150.

[9] Commissioner of Patents v RPL Central Pty Ltd [2015] FCAFC 177.

[10] See Tettman v Technological Resources Pty Ltd [2018] APO 22 [156]–[169].

[11] Technological Resources Pty Ltd v Tettman [2019] FCA 1889 [153]–[154].

[12] See, e.g., Repipe Pty Ltd v Commissioner of Patents [2019] FCA 1956; Encompass Corporation Pty Ltd v InfoTrack Pty Ltd [2019] FCAFC 161; [24]/7.ai, Inc. [2019] APO 50.

[13] See Rokt Pte Ltd v Commissioner of Patents [2018] FCA 1988 for Robertson J’s finding that the invention was patentable in the first instance.